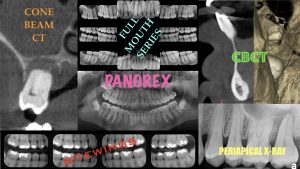

In a recent article on www.facialart.com, “What X-rays Should Patients Have”, I addressed a common question by many patients: “Which X-rays do I really need and how often should they be done?”. In this article, I discussed the problem with traditional recommendations on type and frequency of various dental X-rays and offered a more current protocol. I discussed the role of CBCT in everyday diagnostic imaging and shared a perspective on type and frequency of X-rays based on one’s state of oral health, history of dental treatments, and risk factors for dental disease.

In a recent article on www.facialart.com, “What X-rays Should Patients Have”, I addressed a common question by many patients: “Which X-rays do I really need and how often should they be done?”. In this article, I discussed the problem with traditional recommendations on type and frequency of various dental X-rays and offered a more current protocol. I discussed the role of CBCT in everyday diagnostic imaging and shared a perspective on type and frequency of X-rays based on one’s state of oral health, history of dental treatments, and risk factors for dental disease.

The limitations of 2-dimensional radiography in accurate diagnosis of dental disease has been well documented. And in many instances, even the clinical evaluation may mislead clinicians toward a wrong assessment of teeth conditions. One such instance is presence of thick soft tissue biotype which can easily mask existing defects, deformities, or disease associated with the teeth. This further supports the need for 3-D screening radiography in patients with multiple dental treatments and history of generalized dental disease. We present two cases to demonstrate how active disease was masked by what appeared to be healthy and robust gingival tissue and not diagnosed on conventional radiographs:

Case #1:

This patient was referred for removal of dental implants #3 and #4 due to advanced peri-implantitis and infection evident on routine conventional radiographs. The full mouth series also showed about 40%, 30%, and 10% of bone loss around implants #5, 6, and 8, respectively. These implants were restored with a splinted bridge and patient exhibited no signs or symptoms. The soft tissue was of thick biotype and except the discoloration over implant #5 (which the patient assumed to be amalgam tatoo), appeared quite normal. There was also no pain on palpation and no bleeding on routine brushing, per patient’s report. An FMS and periodic bitewings taken during routine hygiene visits was the only available radiographs. In preparation for explantation of implants #3 and #4, a CBCT was obtained to assess the exact position of the implants and their proximity to the maxillary sinus. Such information is of course vital in proper explantation and management of perforation should it occur. The CBCT also revealed complete missing buccal bone on implants #5, 6, and 8 which simply could not be appreciated on conventional X-rays. Whether the implants were poorly positioned initially or there was bone loss over time was not clear. However, given the implants appeared outside of the maxillary envelope, the former is the most likely etiology. Patient was quite surprised of such findings having been told for years that her implants are fine and only ‘mild’ bone loss on X-ray. In-addition to lack of 3-D imaging, the presence of thick overlying soft tissue had masked the implants and misled the clinicians toward wrong assumptions. This demonstrates that we simply can not depend solely on clinical examination and 2-dimensional x-rays for accurate diagnosis of such conditions.

Case #2:

This patient had seen his dentist regularly with FMS about every 5 years and bitewings at 6-month intervals. Internal resorption involving the central lower incisors had been diagnosed in 2013 followed by selective endodontic therapy. The scope and technique of performed endodontic therapy is known. The lesion ‘appeared’ to have healed in 2017 as seen on conventional periapical X-ray. Then in 2019, patient reported discomfort in the region of his lower anterior teeth. The X-ray revealed recurrent periapical radioleucency. Patient was referred to an endodontist for evaluation who recommended extractions of the two lower central incisors as re-treatment was not advised. The gingival tissue appeared completely normal with no swelling, fistula, or bleeding on probing. The teeth exhibited 1 out of 3 mobility and the probing depth was WNL. A CBCT was recommended before extraction to assess extent of the periapical lesions. It revealed a much more extensive bone loss and disease than noted on the periapical X-rays. These findings led to a modified treatment plan which included selective extractions, exploration, excision of lesions, assessment of adjacent teeth, and bone grafting, followed by endodontic therapy of preserved dentition associated with the lesion.

The surgical exploration confirmed the extensive bone loss and destruction noted in the 3-D scan. Considering patient’s request to preserve as many teeth as possible, even if guarded, the central incisors were extracted, the lesions were excised, and the exposed root surfaces of adjacent teeth were treated by scaling and debridement. The site and the adjacent teeth were grafted using guided bone regeneration techniques. Patient was then referred for endodontic therapy of teeth preserved surrounding the area.

This case, similarly, demonstrates the inconsistency between the clinical presentation and 2-D radiographs, and the extent of the bony defect. The normal appearance of the overlying soft tissue did not correlate with such disease process. Again, a screening CBCT as a follow up to previously performed endodontic therapy in 2017 could have provided critical information to the clinicians and a more controlled management and outcome.